ANSI escape code

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

(Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

ANSI escape sequences are a standard for in-band signaling to control the cursor location, color, and other options on video text terminals and terminal emulators. Certain sequences of bytes, most starting with Esc (ASCII character 27) and '[', are embedded into the text, which the terminal looks for and interprets as commands, not as character codes.

ANSI sequences were introduced in the 1970s to replace vendor-specific sequences and became widespread in the computer equipment market by the early 1980s. They were used in development, scientific and commercial applications and later by the nascent bulletin board systems to offer improved displays compared to earlier systems lacking cursor movement, a primary reason they became a standard adopted by all manufacturers.

Although hardware text terminals have become increasingly rare in the 21st century, the relevance of the ANSI standard persists because most terminal emulators interpret at least some of the ANSI escape sequences in output text. A notable exception was DOS and older versions of the Win32 console of Microsoft Windows.

History[edit]

Almost all manufacturers of video terminals added vendor-specific escape sequences to perform operations such as placing the cursor at arbitrary positions on the screen. One example is the VT52 terminal, which allowed the cursor to be placed at an x,y location on the screen by sending the ESC character, a Y character, and then two characters representing with numerical values equal to the x,y location plus 32 (thus starting at the ASCII space character and avoiding the control characters). The Hazeltine 1500 had a similar feature, invoked using ~, DC1 and then the X and Y positions separated with a comma. While the two terminals had identical functionality in this regard, different control sequences had to be used to invoke them.

As these sequences were different for different terminals, elaborate libraries such as termcap ("terminal capabilities") and utilities such as tput had to be created so programs could use the same API to work with any terminal. In addition, many of these terminals required sending numbers (such as row and column) as the binary values of the characters; for some programming languages, and for systems that did not use ASCII internally, it was often difficult to turn a number into the correct character.

The ANSI standard attempted to address these problems by making a command set that all terminals would use and requiring all numeric information to be transmitted as ASCII numbers. The first standard in the series was ECMA-48, adopted in 1976.[1] It was a continuation of a series of character coding standards, the first one being ECMA-6 from 1965, a 7-bit standard from which ISO 646 originates. The name "ANSI escape sequence" dates from 1979 when ANSI adopted ANSI X3.64. The ANSI X3L2 committee collaborated with the ECMA committee TC 1 to produce nearly identical standards. These two standards were merged into an international standard, ISO 6429.[1] In 1994, ANSI withdrew its standard in favor of the international standard.

The first popular video terminal to support these sequences was the Digital VT100, introduced in 1978.[2] This model was very successful in the market, which sparked a variety of VT100 clones, among the earliest and most popular of which was the much more affordable Zenith Z-19 in 1979.[3] Others included the Qume QVT-108, Televideo TVI-970, Wyse WY-99GT as well as optional "VT100" or "VT103" or "ANSI" modes with varying degrees of compatibility on many other brands. The popularity of these gradually led to more and more software (especially bulletin board systems and other online services) assuming the escape sequences worked, leading to almost all new terminals and emulator programs supporting them.

In 1981, ANSI X3.64 was adopted for use in the US government by FIPS publication 86. Later, the US government stopped duplicating industry standards, so FIPS pub. 86 was withdrawn.[4]

ECMA-48 has been updated several times and is currently at its 5th edition, from 1991.[5] It is also adopted by ISO and IEC as standard ISO/IEC 6429.

Platform support[edit]

Unix-like systems[edit]

Although termcap/terminfo-style libraries were primarily developed on and for Unix, since about 1984 programs running on Unix-like operating systems could almost always assume they were using a terminal or emulator that supported ANSI sequences;[citation needed] this led to widespread use of ANSI by programs running on those platforms. For instance, many games and shell scripts (see below for colored prompt examples), and utilities such as color directory listings, directly write the ANSI sequences and thus cannot be used on a terminal that does not interpret them. Many programs, including text editors such as vi and GNU Emacs, still use termcap or terminfo, or use libraries such as curses that use termcap or terminfo, and thus in theory support non-ANSI terminals, but this is so rarely tested nowadays that they are unlikely to work with those terminals.[citation needed] Terminal emulators for communicating with local programs as well as remote machines and the text system console almost always support ANSI escape codes.

DOS and Windows[edit]

MS-DOS 1.x did not support the ANSI or any other escape sequences. Only a few control characters (BEL, CR, LF, BS) were interpreted by the underlying BIOS, making it almost[nb 1] impossible to do any kind of full-screen application. Any display effects had to be done with BIOS calls, which were notoriously slow, or by directly manipulating the IBM PC hardware.

DOS 2.0 introduced the ability to add a device driver for the ANSI escape sequences – the de facto standard being ANSI.SYS, but others like ANSI.COM,[6] NANSI.SYS[7] and ANSIPLUS.EXE are used as well (these are considerably faster as they bypass the BIOS). Slowness and the fact that it was not installed by default made software rarely take advantage of it; instead, applications continued to directly manipulate the hardware to get the text display needed.[citation needed] ANSI.SYS and similar drivers continued to work in Windows 9x up to Windows Me, and in NT-derived systems for 16-bit legacy programs executing under the NTVDM.

Many emulators of DOS were able to interpret the sequences. PTS-DOS[8][9] as well as Concurrent DOS, Multiuser DOS[10] and REAL/32 have built-in support (plus a number of extensions) and do not require a separate ANSI driver to be loaded. OS/2 had an ANSI command that enabled the sequences.

The Windows Console did not support ANSI escape sequences, nor did Microsoft provide any method to enable them. Some replacements or additions for the console window such as JP Software's TCC (formerly 4NT), Michael J. Mefford's ANSI.COM, Jason Hood's ANSICON[11] and Maximus5's ConEmu interpreted ANSI escape sequences printed by programs. A Python package[12] internally interpreted ANSI escape sequences in text being printed, translating them to calls to manipulate the color and cursor position, to make it easier to port Python code using ANSI to Windows.

In 2016, Microsoft released the Windows 10 Version 1511 update which unexpectedly implemented support for ANSI escape sequences.[13] The change was designed to complement the Windows Subsystem for Linux, adding to the Windows Console Host used by Command Prompt support for character escape codes used by terminal-based software for Unix-like systems. This is not the default behavior and must be enabled programmatically with the Win32 API via SetConsoleMode(handle, ENABLE_VIRTUAL_TERMINAL_PROCESSING).[14] This was enabled by CMD.EXE but not initially by PowerShell;[15] however, Windows PowerShell 5.1 now enables this by default. The ability to make a string constant containing ESC was added in PowerShell 6 with (for example) "`e[32m";[16] for PowerShell 5 you had to use [char]0x1B+"[32m".

Windows Terminal, introduced in 2019, supports the sequences by default, and it appears Microsoft intends to merge or replace Windows Console with it.

Atari ST[edit]

The Atari ST used the command system adapted from the VT52 with some expansions for color support,[17] rather than supporting ANSI escape codes.

AmigaOS[edit]

AmigaOS not only interprets ANSI code sequences for text output to the screen, the AmigaOS printer driver also interprets them (with extensions proprietary to AmigaOS) and translates them into the codes required for the particular printer that is actually attached.[18]

Escape sequences[edit]

Sequences have different lengths. All sequences start with ESC (27 / hex 0x1B / oct 033), followed by a second byte in the range 0x40–0x5F (ASCII @A–Z[\]^_).[5]:5.3.a

The standard says that in 8-bit environments these two-byte sequences can be merged into single C1 control code in the 0x80–0x9F range.[5]:5.3.b However, on modern devices those codes are often used for other purposes, such as parts of UTF-8 or for CP-1252 characters, so only the 2-byte sequence is typically used.

Other C0 codes besides ESC — commonly BEL, BS, CR, LF, FF, TAB, VT, SO, and SI — produce similar or identical effects to some control sequences when output.

| Sequence | C1 | Short | Name | Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESC N | 0x8E | SS2 | Single Shift Two | Select a single character from one of the alternative character sets. In xterm, SS2 selects the G2 character set, and SS3 selects the G3 character set.[19] |

| ESC O | 0x8F | SS3 | Single Shift Three | |

| ESC P | 0x90 | DCS | Device Control String | Terminated by ST. Xterm's uses of this sequence include defining User-Defined Keys, and requesting or setting Termcap/Terminfo data.[19] |

| ESC [ | 0x9B | CSI | Control Sequence Introducer | Most of the useful sequences, see next section. |

| ESC \ | 0x9C | ST | String Terminator | Terminates strings in other controls.[5]:8.3.143 |

| ESC ] | 0x9D | OSC | Operating System Command | Starts a control string for the operating system to use, terminated by ST.[5]:8.3.89 In xterm, they may also be terminated by BEL.[19] For example, xterm allows the window title to be set by \x1b]0;this is the window title\x07.

|

| ESC X | 0x98 | SOS | Start of String | Takes an argument of a string of text, terminated by ST. The uses for these string control sequences are defined by the application[5]:8.3.2,8.3.128 or privacy discipline.[5]:8.3.94 These functions are rarely implemented and the arguments are ignored by xterm.[19] |

| ESC ^ | 0x9E | PM | Privacy Message | |

| ESC _ | 0x9F | APC | Application Program Command | |

| ESC c | RIS | Reset to Initial State | Resets the device to its original state. This may include (if applicable): reset graphic rendition, clear tabulation stops, reset to default font, and more.[20] |

Pressing special keys on the keyboard, as well as outputting many xterm CSI, DCS, or OSC sequences, often produces a CSI, DCS, or OSC sequence, sent from the terminal to the computer as though the user typed it.

CSI sequences[edit]

For CSI, or "Control Sequence Introducer" commands, the ESC [ is followed by any number (including none) of "parameter bytes" in the range 0x30–0x3F (ASCII 0–9:;<=>?), then by any number of "intermediate bytes" in the range 0x20–0x2F (ASCII space and !"#$%&'()*+,-./), then finally by a single "final byte" in the range 0x40–0x7E (ASCII @A–Z[\]^_`a–z{|}~).[5]:5.4

All common sequences just use the parameters as a series of semicolon-separated numbers such as 1;2;3. Missing numbers are treated as 0 (1;;3 acts like the middle number is 0, and no parameters at all in ESC[m acts like a 0 reset code). Some sequences (such as CUU) treat 0 as 1 in order to make missing parameters useful.[5]:F.4.2 Bytes other than digits and semicolon seem to not be used.[citation needed]

An example of a CSI sequence that cleans up the entire line: \e[2K

A subset of arrangements was declared "private" so that terminal manufacturers could insert their own sequences without conflicting with the standard. Sequences containing the parameter bytes <=>? or the final bytes 0x70–0x7E (p–z{|}~) are private.

The behavior of the terminal is undefined in the case where a CSI sequence contains any character outside of the range 0x20–0x7E. These illegal characters are either C0 control characters (the range 0–0x1F), DEL (0x7F), or bytes with the high bit set. Possible responses are to ignore the byte, to process it immediately, and furthermore whether to continue with the CSI sequence, to abort it immediately, or to ignore the rest of it.[citation needed]

Terminal output sequences[edit]

| Code | Short | Name | Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSI n A | CUU | Cursor Up | Moves the cursor n (default 1) cells in the given direction. If the cursor is already at the edge of the screen, this has no effect.

|

| CSI n B | CUD | Cursor Down | |

| CSI n C | CUF | Cursor Forward | |

| CSI n D | CUB | Cursor Back | |

| CSI n E | CNL | Cursor Next Line | Moves cursor to beginning of the line n (default 1) lines down. (not ANSI.SYS)

|

| CSI n F | CPL | Cursor Previous Line | Moves cursor to beginning of the line n (default 1) lines up. (not ANSI.SYS)

|

| CSI n G | CHA | Cursor Horizontal Absolute | Moves the cursor to column n (default 1). (not ANSI.SYS)

|

| CSI n ; m H | CUP | Cursor Position | Moves the cursor to row n, column m. The values are 1-based, and default to 1 (top left corner) if omitted. A sequence such as CSI ;5H is a synonym for CSI 1;5H as well as CSI 17;H is the same as CSI 17H and CSI 17;1H

|

| CSI n J | ED | Erase in Display | Clears part of the screen. If n is 0 (or missing), clear from cursor to end of screen. If n is 1, clear from cursor to beginning of the screen. If n is 2, clear entire screen (and moves cursor to upper left on DOS ANSI.SYS). If n is 3, clear entire screen and delete all lines saved in the scrollback buffer (this feature was added for xterm and is supported by other terminal applications).

|

| CSI n K | EL | Erase in Line | Erases part of the line. If n is 0 (or missing), clear from cursor to the end of the line. If n is 1, clear from cursor to beginning of the line. If n is 2, clear entire line. Cursor position does not change.

|

| CSI n S | SU | Scroll Up | Scroll whole page up by n (default 1) lines. New lines are added at the bottom. (not ANSI.SYS)

|

| CSI n T | SD | Scroll Down | Scroll whole page down by n (default 1) lines. New lines are added at the top. (not ANSI.SYS)

|

| CSI n ; m f | HVP | Horizontal Vertical Position | Same as CUP, but counts as a format effector function (like CR or LF) rather than an editor function (like CUD or CNL). This can lead to different handling in certain terminal modes.[5]:Annex A |

| CSI n m | SGR | Select Graphic Rendition | Sets the appearance of the following characters, see SGR parameters below. |

| CSI 5i | AUX Port On | Enable aux serial port usually for local serial printer | |

| CSI 4i | AUX Port Off | Disable aux serial port usually for local serial printer

| |

| CSI 6n | DSR | Device Status Report | Reports the cursor position (CPR) to the application as (as though typed at the keyboard) ESC[n;mR, where n is the row and m is the column.)

|

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| CSI s | SCP/SCOSC: Save Current Cursor Position. Saves the cursor position/state in SCO console mode.[21] In vertical split screen mode, instead used to set (as CSI n ; n s) or reset left and right margins.[22]

|

| CSI u | RCP/SCORC: Restore Saved Cursor Position. Restores the cursor position/state in SCO console mode.[23] |

| CSI ? 25 h | DECTCEM Shows the cursor, from the VT320. |

| CSI ? 25 l | DECTCEM Hides the cursor. |

| CSI ? 1049 h | Enable alternative screen buffer |

| CSI ? 1049 l | Disable alternative screen buffer |

| CSI ? 2004 h | Turn on bracketed paste mode. Text pasted into the terminal will be surrounded by ESC [200~ and ESC [201~, and characters in it should not be treated as commands (for example in Vim).[24] From Unix terminal emulators.

|

| CSI ? 2004 l | Turn off bracketed paste mode. |

SGR parameters[edit]

SGR (Select Graphic Rendition) sets display attributes. Several attributes can be set in the same sequence, separated by semicolons.[25] Each display attribute remains in effect until a following occurrence of SGR resets it.[5] If no codes are given, CSI m is treated as CSI 0 m (reset / normal).

In ECMA-48 SGR is called "Select Graphic Rendition".[5]:8.3.117 In Linux manual pages the term "Set Graphics Rendition" is used.[25]

| Code | Effect | Note |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Reset / Normal | All attributes off |

| 1 | Bold or increased intensity | |

| 2 | Faint (decreased intensity) | aka Dim |

| 3 | Italic | Not widely supported. Sometimes treated as inverse. |

| 4 | Underline | |

| 5 | Slow Blink | less than 150 per minute |

| 6 | Rapid Blink | MS-DOS ANSI.SYS; 150+ per minute; not widely supported |

| 7 | Reverse video | swap foreground and background colors, aka invert |

| 8 | Conceal | aka Hide, not widely supported. |

| 9 | Crossed-out | aka Strike, characters legible, but marked for deletion. |

| 10 | Primary(default) font | |

| 11–19 | Alternative font | Select alternative font n − 10 |

| 20 | Fraktur | Rarely supported |

| 21 | Doubly underline or Bold off | Double-underline per ECMA-48.[5]:8.3.117 See discussion |

| 22 | Normal color or intensity | Neither bold nor faint |

| 23 | Not italic, not Fraktur | |

| 24 | Underline off | Not singly or doubly underlined |

| 25 | Blink off | |

| 27 | Reverse/invert off | |

| 28 | Reveal | conceal off |

| 29 | Not crossed out | |

| 30–37 | Set foreground color | See color table below |

| 38 | Set foreground color | Next arguments are 5;n or 2;r;g;b, see below

|

| 39 | Default foreground color | implementation defined (according to standard) |

| 40–47 | Set background color | See color table below |

| 48 | Set background color | Next arguments are 5;n or 2;r;g;b, see below

|

| 49 | Default background color | implementation defined (according to standard) |

| 51 | Framed | |

| 52 | Encircled | |

| 53 | Overlined | |

| 54 | Not framed or encircled | |

| 55 | Not overlined | |

| 60 | ideogram underline or right side line | Rarely supported |

| 61 | ideogram double underline or double line on the right side | |

| 62 | ideogram overline or left side line | |

| 63 | ideogram double overline or double line on the left side | |

| 64 | ideogram stress marking | |

| 65 | ideogram attributes off | reset the effects of all of 60–64

|

| 90–97 | Set bright foreground color | aixterm (not in standard) |

| 100–107 | Set bright background color | aixterm (not in standard) |

Colors[edit]

3/4 bit[edit]

The original specification only had 8 colors, and just gave them names. The SGR parameters 30-37 selected the foreground color, while 40-47 selected the background. Quite a few terminals implemented "bold" (SGR code 1) as a brighter color rather than a different font, thus providing 8 additional foreground colors. Usually you could not get these as background colors, though sometimes inverse video (SGR code 7) would allow that. Examples: to get black letters on white background use ESC[30;47m, to get red use ESC[31m, to get bright red use ESC[1;31m. To reset colors to their defaults, use ESC[39;49m (not supported on some terminals), or reset all attributes with ESC[0m. Later terminals added the ability to directly specify the "bright" colors with 90-97 and 100-107.

When hardware started using 8-bit digital-to-analog converters (DACs) several pieces of software assigned 24-bit color numbers to these names. The chart below shows values sent to the DAC for some common hardware and software.[citation needed]

| Name | FG Code | BG Code | VGA[nb 2] | Windows Console[nb 3] | Windows PowerShell[nb 4] | Visual Studio Code

Debug Console (Default Dark+ Theme) |

Windows 10 Console[nb 5] PowerShell 6 |

Terminal.app | PuTTY | mIRC | xterm | X[nb 6] | Ubuntu[nb 7] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black | 30 | 40 | 0,0,0 | 12,12,12 | 0,0,0 | 1,1,1 | |||||||

| Red | 31 | 41 | 170,0,0 | 128,0,0 | 205, 49, 49 | 197,15,31 | 194,54,33 | 187,0,0 | 127,0,0 | 205,0,0 | 255,0,0 | 222,56,43 | |

| Green | 32 | 42 | 0,170,0 | 0,128,0 | 13, 188, 121 | 19,161,14 | 37,188,36 | 0,187,0 | 0,147,0 | 0,205,0 | 0,255,0 | 57,181,74 | |

| Yellow | 33 | 43 | 170,85,0[nb 8] | 128,128,0 | 238,237,240 | 229, 229, 16 | 193,156,0 | 173,173,39 | 187,187,0 | 252,127,0 | 205,205,0 | 255,255,0 | 255,199,6 |

| Blue | 34 | 44 | 0,0,170 | 0,0,128 | 36, 114, 200 | 0,55,218 | 73,46,225 | 0,0,187 | 0,0,127 | 0,0,238[26] | 0,0,255 | 0,111,184 | |

| Magenta | 35 | 45 | 170,0,170 | 128,0,128 | 1,36,86 | 188, 63, 188 | 136,23,152 | 211,56,211 | 187,0,187 | 156,0,156 | 205,0,205 | 255,0,255 | 118,38,113 |

| Cyan | 36 | 46 | 0,170,170 | 0,128,128 | 17, 168, 205 | 58,150,221 | 51,187,200 | 0,187,187 | 0,147,147 | 0,205,205 | 0,255,255 | 44,181,233 | |

| White | 37 | 47 | 170,170,170 | 192,192,192 | 229, 229, 229 | 204,204,204 | 203,204,205 | 187,187,187 | 210,210,210 | 229,229,229 | 255,255,255 | 204,204,204 | |

| Bright Black | 90 | 100 | 85,85,85 | 128,128,128 | 102, 102, 102 | 118,118,118 | 129,131,131 | 85,85,85 | 127,127,127 | 127,127,127 | 128,128,128 | ||

| Bright Red | 91 | 101 | 255,85,85 | 255,0,0 | 241, 76, 76 | 231,72,86 | 252,57,31 | 255,85,85 | 255,0,0 | 255,0,0 | 255,0,0 | ||

| Bright Green | 92 | 102 | 85,255,85 | 0,255,0 | 35, 209, 139 | 22,198,12 | 49,231,34 | 85,255,85 | 0,252,0 | 0,255,0 | 144,238,144 | 0,255,0 | |

| Bright Yellow | 93 | 103 | 255,255,85 | 255,255,0 | 245, 245, 67 | 249,241,165 | 234,236,35 | 255,255,85 | 255,255,0 | 255,255,0 | 255,255,224 | 255,255,0 | |

| Bright Blue | 94 | 104 | 85,85,255 | 0,0,255 | 59, 142, 234 | 59,120,255 | 88,51,255 | 85,85,255 | 0,0,252 | 92,92,255[27] | 173,216,230 | 0,0,255 | |

| Bright Magenta | 95 | 105 | 255,85,255 | 255,0,255 | 214, 112, 214 | 180,0,158 | 249,53,248 | 255,85,255 | 255,0,255 | 255,0,255 | 255,0,255 | ||

| Bright Cyan | 96 | 106 | 85,255,255 | 0,255,255 | 41, 184, 219 | 97,214,214 | 20,240,240 | 85,255,255 | 0,255,255 | 0,255,255 | 224,255,255 | 0,255,255 | |

| Bright White | 97 | 107 | 255,255,255 | 255,255,255 | 229, 229, 229 | 242,242,242 | 233,235,235 | 255,255,255 | 255,255,255 | 255,255,255 | 255,255,255 | ||

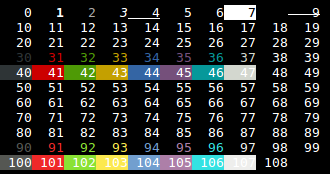

8-bit[edit]

As 256-color lookup tables became common on graphic cards, escape sequences were added to select from a pre-defined set of 256 colors:[citation needed]

ESC[ 38;5;⟨n⟩ m Select foreground color ESC[ 48;5;⟨n⟩ m Select background color 0- 7: standard colors (as in ESC [ 30–37 m) 8- 15: high intensity colors (as in ESC [ 90–97 m) 16-231: 6 × 6 × 6 cube (216 colors): 16 + 36 × r + 6 × g + b (0 ≤ r, g, b ≤ 5) 232-255: grayscale from black to white in 24 steps

The ITU's T.416 Information technology - Open Document Architecture (ODA) and interchange format: Character content architectures[28] uses ':' as separator characters instead:

ESC[ 38:5:⟨n⟩ m Select foreground color ESC[ 48:5:⟨n⟩ m Select background color

| 256-color mode — foreground: ESC[38;5;#m background: ESC[48;5;#m | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard colors | High-intensity colors | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 216 colors | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 38 | 39 | 40 | 41 | 42 | 43 | 44 | 45 | 46 | 47 | 48 | 49 | 50 | 51 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 52 | 53 | 54 | 55 | 56 | 57 | 58 | 59 | 60 | 61 | 62 | 63 | 64 | 65 | 66 | 67 | 68 | 69 | 70 | 71 | 72 | 73 | 74 | 75 | 76 | 77 | 78 | 79 | 80 | 81 | 82 | 83 | 84 | 85 | 86 | 87 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 88 | 89 | 90 | 91 | 92 | 93 | 94 | 95 | 96 | 97 | 98 | 99 | 100 | 101 | 102 | 103 | 104 | 105 | 106 | 107 | 108 | 109 | 110 | 111 | 112 | 113 | 114 | 115 | 116 | 117 | 118 | 119 | 120 | 121 | 122 | 123 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 124 | 125 | 126 | 127 | 128 | 129 | 130 | 131 | 132 | 133 | 134 | 135 | 136 | 137 | 138 | 139 | 140 | 141 | 142 | 143 | 144 | 145 | 146 | 147 | 148 | 149 | 150 | 151 | 152 | 153 | 154 | 155 | 156 | 157 | 158 | 159 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 160 | 161 | 162 | 163 | 164 | 165 | 166 | 167 | 168 | 169 | 170 | 171 | 172 | 173 | 174 | 175 | 176 | 177 | 178 | 179 | 180 | 181 | 182 | 183 | 184 | 185 | 186 | 187 | 188 | 189 | 190 | 191 | 192 | 193 | 194 | 195 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 196 | 197 | 198 | 199 | 200 | 201 | 202 | 203 | 204 | 205 | 206 | 207 | 208 | 209 | 210 | 211 | 212 | 213 | 214 | 215 | 216 | 217 | 218 | 219 | 220 | 221 | 222 | 223 | 224 | 225 | 226 | 227 | 228 | 229 | 230 | 231 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Grayscale colors | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

24-bit[edit]

As "true color" graphic cards with 16 to 24 bits of color became common, Xterm,[19] KDE's Konsole,[29] iTerm, as well as all libvte based terminals[30] (including GNOME Terminal) support 24-bit foreground and background color setting.[better source needed][31]

ESC[ 38;2;⟨r⟩;⟨g⟩;⟨b⟩ m Select RGB foreground color ESC[ 48;2;⟨r⟩;⟨g⟩;⟨b⟩ m Select RGB background color

The ITU's T.416 Information technology - Open Document Architecture (ODA) and interchange format: Character content architectures[28] which was adopted as ISO/IEC International Standard 8613-6 gives an alternative version that seems to be less supported:[dubious ]

ESC[ 38:2:⟨Color-Space-ID⟩:⟨r⟩:⟨g⟩:⟨b⟩:⟨unused⟩:⟨CS tolerance⟩:⟨Color-Space associated with tolerance: 0 for "CIELUV"; 1 for "CIELAB"⟩; m Select RGB foreground color ESC[ 48:2:⟨Color-Space-ID⟩:⟨r⟩:⟨g⟩:⟨b⟩:⟨unused⟩:⟨CS tolerance⟩:⟨Color-Space associated with tolerance: 0 for "CIELUV"; 1 for "CIELAB"⟩; m Select RGB background color

Note that this uses the otherwise reserved ':' character to separate the sub-options which may have been a source of confusion for real-world implementations.[citation needed] It also documents using '3' as the second parameter to specify colors using a Cyan-Magenta-Yellow scheme and '4' for a Cyan-Magenta-Yellow-Black one, the latter using the position marked as "unused" in the above examples for the Black component.

Also note that many implementation that recognize ':' as the separator erroneously forget about the color space identifier parameter and hence shift the position of the remaining ones.[citation needed][clarification needed]

Examples[edit]

CSI 2 J — This clears the screen and, on some devices, locates the cursor to the y,x position 1,1 (upper left corner).

CSI 32 m — This makes text green. The green may be a dark, dull green, so you may wish to enable Bold with the sequence CSI 1 m which would make it bright green, or combined as CSI 32 ; 1 m. Some implementations use the Bold state to make the character Bright.

CSI 0 ; 6 8 ; "DIR" ; 13 p — This reassigns the key F10 to send to the keyboard buffer the string "DIR" and ENTER, which in the DOS command line would display the contents of the current directory. (MS-DOS ANSI.SYS only) This was sometimes used for ANSI bombs. This is a private-use code (as indicated by the letter p), using a non-standard extension to include a string-valued parameter. Following the letter of the standard would consider the sequence to end at the letter D.

CSI s — This saves the cursor position. Using the sequence CSI u will restore it to the position. Say the current cursor position is 7(y) and 10(x). The sequence CSI s will save those two numbers. Now you can move to a different cursor position, such as 20(y) and 3(x), using the sequence CSI 20 ; 3 H or CSI 20 ; 3 f. Now if you use the sequence CSI u the cursor position will return to 7(y) and 10(x). Some terminals require the DEC sequences ESC 7 / ESC 8 instead which is more widely supported.

Example of use in shell scripting[edit]

ANSI escape codes are often used in UNIX and UNIX-like terminals to provide syntax highlighting. For example, on compatible terminals, the following list command color-codes file and directory names by type.

ls --color

Users can employ escape codes in their scripts by including them as part of standard output or standard error. For example, the following GNU sed command embellishes the output of the make command by displaying lines containing words starting with "WARN" in reverse video and words starting with "ERR" in bright yellow on a dark red background (letter case is ignored). The representations of the codes are highlighted.[32]

make 2>&1 | sed -e 's/.*\bWARN.*/\x1b[7m&\x1b[0m/i' -e 's/.*\bERR.*/\x1b[93;41m&\x1b[0m/i'

The following Bash function flashes the terminal (by alternately sending reverse and normal video mode codes) until the user presses a key.[33]

flasher () { while true; do printf \\e[?5h; sleep 0.1; printf \\e[?5l; read -s -n1 -t1 && break; done; }

This can be used to alert a programmer when a lengthy command terminates, such as with make ; flasher .[34]

printf \\033c

This will reset the console, similar to the command reset on modern Linux systems; however it should work even on older Linux systems and on other (non-Linux) UNIX variants.

Example of use in C[edit]

1 #include <stdio.h>

2

3 int main(void)

4 {

5 int i, j, n;

6

7 for (i = 0; i < 11; i++) {

8 for (j = 0; j < 10; j++) {

9 n = 10*i + j;

10 if (n > 108) break;

11 printf("\033[%dm %3d\033[m", n, n);

12 }

13 printf("\n");

14 }

15 return (0);

16 }

Terminal input sequences[edit]

This section does not cite any sources. (September 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

When typing input on a terminal keypresses outside the normal main alphanumeric keyboard area can be sent to the host as ANSI sequences. For keys that have an equivalent output function, such as the cursor keys, these often mirror the output sequences. However, for most keypresses there isn't an equivalent output sequence to use.

There are several encoding schemes, and unfortunately most terminals mix sequences from different schemes, so host software has to be able to deal with input sequences using any scheme.

(draft section)

<char> -> char

<esc> <nochar> -> esc

<esc> <esc> -> esc

<esc> <char> -> Alt-keypress or keycode sequence

<esc> '[' <nochar> -> Alt-[

<esc> '[' (<num>) (';'<num>) '~' -> keycode sequence, <num> defaults to 1

If the terminating character is '~', the first number must be present and is a keycode number, the second number is an optional modifier value. If the terminating character is a letter, the letter is the keycode value, and the optional number is the modifier value.

The modifier value defaults to 1, and after subtracting 1 is a bitmap of modifier keys being pressed: Meta-Ctrl-Alt-Shift. So, for example, <esc>[4;2~ is Shift-End, <esc>[20~ is function key 9, <esc>[5C is Ctrl-Right.

vt sequences: <esc>[1~ - Home <esc>[16~ - <esc>[31~ - F17 <esc>[2~ - Insert <esc>[17~ - F6 <esc>[32~ - F18 <esc>[3~ - Delete <esc>[18~ - F7 <esc>[33~ - F19 <esc>[4~ - End <esc>[19~ - F8 <esc>[34~ - F20 <esc>[5~ - PgUp <esc>[20~ - F9 <esc>[35~ - <esc>[6~ - PgDn <esc>[21~ - F10 <esc>[7~ - Home <esc>[22~ - <esc>[8~ - End <esc>[23~ - F11 <esc>[9~ - <esc>[24~ - F12 <esc>[10~ - F0 <esc>[25~ - F13 <esc>[11~ - F1 <esc>[26~ - F14 <esc>[12~ - F2 <esc>[27~ - <esc>[13~ - F3 <esc>[28~ - F15 <esc>[14~ - F4 <esc>[29~ - F16 <esc>[15~ - F5 <esc>[30~ - xterm sequences: <esc>[A - Up <esc>[K - <esc>[U - <esc>[B - Down <esc>[L - <esc>[V - <esc>[C - Right <esc>[M - <esc>[W - <esc>[D - Left <esc>[N - <esc>[X - <esc>[E - <esc>[O - <esc>[Y - <esc>[F - End <esc>[1P - F1 <esc>[Z - <esc>[G - Keypad 5 <esc>[1Q - F2 <esc>[H - Home <esc>[1R - F3 <esc>[I - <esc>[1S - F4 <esc>[J - <esc>[T -

<esc>[A to <esc>[D are the same as the ANSI output sequences. The <num> is normally omitted if no modifier keys are pressed, but most implementations always emit the <num> for F1-F4. (draft section)

Xterm has a comprehensive documentation page on the various function-key and mouse input sequence schemes from DEC's VT terminals and various other terminals it emulates.[19] Thomas Dickey has added a lot of support to it over time;[35] he also maintains a list of default keys used by other terminal emulators for comparison.[36]

Invalid and ambiguous sequences in use[edit]

- The Linux console uses

OSC P n rr gg bbto change the palette, which, if hard-coded into an application, may hang other terminals. However, appendingSTwill be ignored by Linux and form a proper, ignorable sequence for other terminals.[citation needed] - On the Linux console, certain function keys generate sequences of the form

CSI [ char. The CSI sequence should terminate on the [. - Old versions of Terminator generate

SS3 1; modifiers charwhen F1–F4 are pressed with modifiers. The faulty behavior was copied from GNOME Terminal.[citation needed] - xterm replies

CSI row ; column Rif asked for cursor position andCSI 1 ; modifiers Rif the F3 key is pressed with modifiers, which collide in the case of row == 1. This can be avoided by using the ? private modifier asCSI ? 6 n, which will be reflected in the response asCSI ? row ; column R. - many terminals prepend

ESCto any character that is typed with the alt key down. This creates ambiguity for uppercase letters and symbols @[\]^_, which would form C1 codes.[clarification needed] - Konsole generates

SS3 modifiers charwhen F1–F4 are pressed with modifiers.[clarification needed]

See also[edit]

- ANSI art

- Control character

- Advanced Video Attribute Terminal Assembler and Recreator (AVATAR)

- ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2

- C0 and C1 control codes

Notes[edit]

- ^ The screen display could be replaced by drawing the entire new screen's contents at the bottom, scrolling the previous screen up sufficiently to erase all the old text. The user would see the scrolling, and the hardware cursor would be left at the very bottom. Some early batch files achieved rudimentary "full screen" displays in this way.

- ^ Typical colors that are used when booting PCs and leaving them in text mode, which used a 16-entry color table. The colors are different in the EGA/VGA graphic modes.

- ^ As of Windows XP

- ^ Until PowerShell 6

- ^ Campbell theme.

Used as of Windows 10 1709 - ^ Above color name from X11 rgb.txt color database, with "light" prefixed for the bright colors.

- ^ For virtual terminals, from /etc/vtrgb.

- ^ On terminals based on CGA compatible hardware, such as ANSI.SYS running on DOS, this normal intensity foreground color is rendered as Orange. CGA RGBI monitors contained hardware to modify the dark yellow color to an orange/brown color by reducing the green component. See this ansi art Archived 25 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine as an example.

References[edit]

- ^ a b "Standard ECMA-48: Control Functions for Character-Imaging I/O Devices" (PDF) (Second ed.). Ecma International. August 1979. Brief History.

- ^ Williams, Paul (2006). "Digital's Video Terminals". VT100.net. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ^ Heathkit Company (1979). "Heathkit Catalog 1979". Heathkit Company. Archived from the original on 13 January 2012. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ^ "Withdrawn FIPS Listed by Number" (PDF). National Institute of Standards and Technology. 15 December 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Standard ECMA-48: Control Functions for Coded Character Sets" (PDF) (Fifth ed.). Ecma International. June 1991.

- ^ Mefford, Michael (7 February 1989). "ANSI.com: Download It Here". PC Magazine. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ^ Kegel, Dan; Auer, Eric (28 February 1999). "Nansi and NNansi – ANSI Drivers for MS-DOS". Dan Kegel's Web Hostel. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ^ "PTS-DOS 2000 Pro User Manual" (PDF). Buggingen, Germany: Paragon Technology GmbH. 1999. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 May 2018. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- ^ Günther, Jens; Ernst, Tobias (25 April 2004) [1996]. Ellsässer, Wolfgang (ed.). "Inoffizielle deutschsprachige PTS-DOS-FAQ (PTS/FAQD)" [Inofficial German PTS-DOS FAQ] (in German). Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- ^ CCI Multiuser DOS 7.22 GOLD Online Documentation. Concurrent Controls, Inc. (CCI). 10 February 1997. HELP.HLP.

- ^ Hood, Jason (2005). "Process ANSI escape sequences for Windows console programs". Jason Hood's Home page. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- ^ "colorama 0.2.5". Python Package Index. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ bitcrazed. "Console Virtual Terminal Sequences - Windows Console". docs.microsoft.com. Retrieved 30 May 2018.

- ^ "Windows 10 Creators Update: What's new in Bash/WSL & Windows Console". Comment by ulrichb and reply by Rick Turner.

- ^ Grehan, Oisin (4 February 2016). "Windows 10 TH2 (v1511) Console Host Enhancements". Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- ^ "PowerShell Help: About Special Characters".

- ^ "Using C-Kermit", p. 88.

- ^ "Amiga Printer Command Definitions". Commodore. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f Moy, Edward; Gildea, Stephen; Dickey, Thomas (2019). "Xterm Control Sequences (ctlseqs)". Invisible Island.

- ^ ISO/TC 97/SC 2 (30 December 1976). Reset to Initial State (RIS) (PDF). ITSCJ/IPSJ. ISO-IR-35.

- ^ "SCOSC—Save Current Cursor Position". VT510 Video Terminal Programmer Information. DEC.

- ^ "DECSLRM—Set Left and Right Margins". VT510 Video Terminal Programmer Information. DEC.

- ^ "SCORC—Restore Saved Cursor Position". VT510 Video Terminal Programmer Information. DEC.

- ^ Conrad Irwin (April 2013). "bracketed paste mode". cirw.in.

- ^ a b "console_codes(4) - Linux manual page". man7.org. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ^ Changed from 0,0,205 in July 2004 "Patch #192 – 2004/7/12 – XFree86 4.4.99.9".

- ^ Changed from 0,0,255 in July 2004 "Patch #192 – 2004/7/12 – XFree86 4.4.99.9".

- ^ a b "T.416 Information technology - Open Document Architecture (ODA) and interchange format: Character content architectures".

- ^ "color-spaces.pl (a copy of 256colors2.pl from xterm dated 1999-07-11)". KDE. 6 December 2006.

- ^ "libvte's bug report and patches". GNOME Bugzilla. 4 April 2014. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- ^ "README.moreColors". KDE. 22 April 2010.

- ^ "Chapter 9. System tips". debian.org.

- ^ "VT100.net: Digital VT100 User Guide". Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ^ "bash – How to get a notification when my commands are done – Ask Different". Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ^ Dickey, Thomas. "Xterm FAQ: Comparing versions, by counting controls". Invisible Island. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ^ Dickey, Thomas (2016). "Table of function-keys for XTerm and other Terminal Emulators". Invisible Island. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

External links[edit]

- Standard ECMA-48, Control Functions For Coded Character Sets. (5th edition, June 1991), European Computer Manufacturers Association, Geneva 1991 (also published by ISO and IEC as standard ISO/IEC 6429)

- vt100.net DEC Documents

- "ANSI.SYS -- ansi terminal emulation escape sequences". Archived from the original on 6 February 2006. Retrieved 22 February 2007.

- Xterm / Escape Sequences

- AIXterm / Escape Sequences

- A collection of escape sequences for terminals that are vaguely compliant with ECMA-48 and friends.

- ANSI Escape Sequences

- ITU-T Rec. T.416 (03/93) Information technology – Open Document Architecture (ODA) and interchange format: Character content architectures